"Experiences of a Pioneer" is the original title of a document written by Stephen Murphy Sisk in September of 1913. It was titled "A Trip to Idaho in 1862" when it was printed in the Idaho Statesman newspaper of Boise, Idaho in September of 1913. Here are images of the original document:

<page 01> <page 02> <page 03> <page 04> <page 05> <page 06> <page 07>

<page 08> <page 09> <page 10> <page 11> <page 12> <page 13>

A Trip to Idaho in 1862.

Initial Chapter in the Story of Idaho Men and Women Trail Blazers.

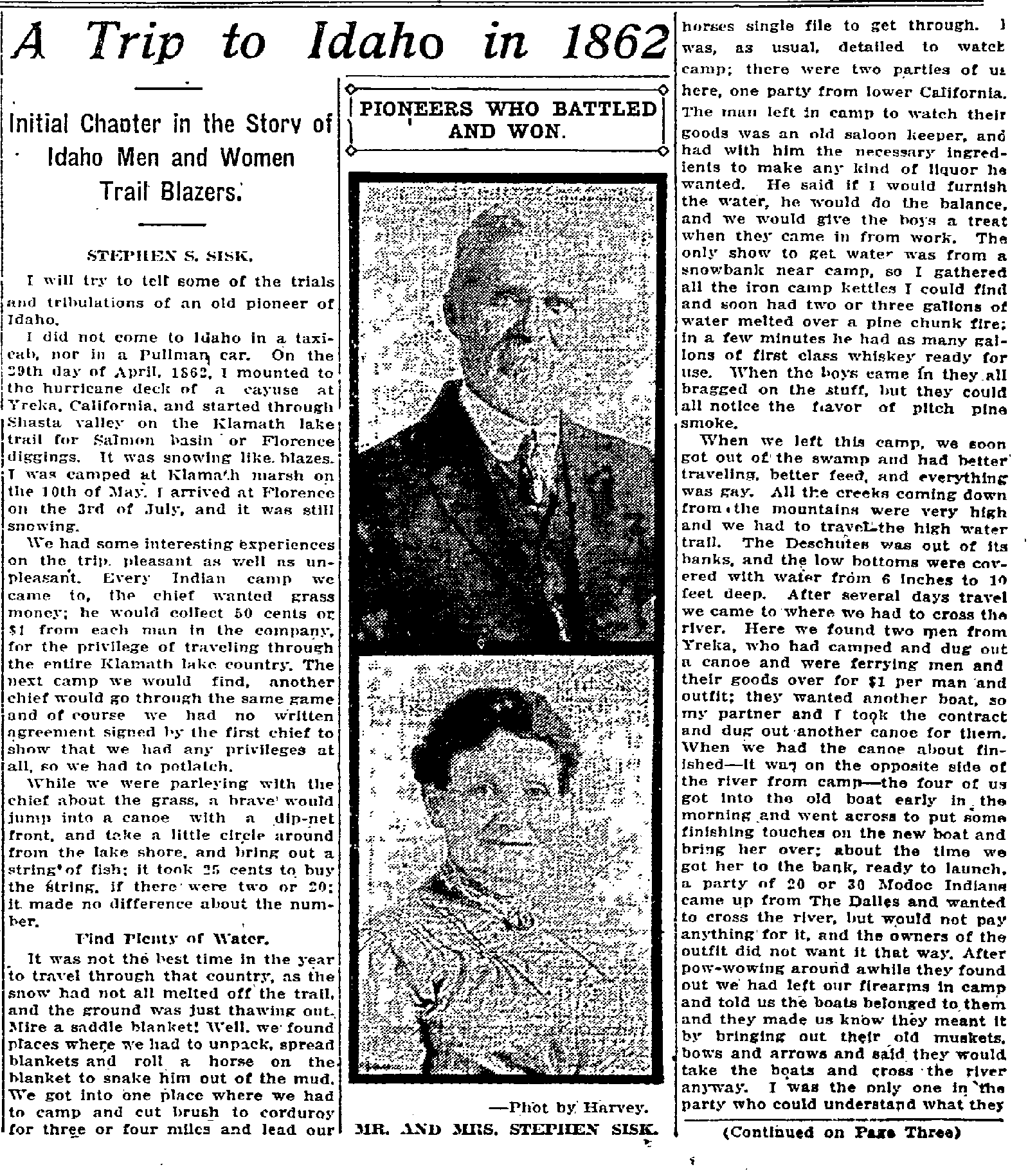

STEPHEN S.[sic M.] SISK.

I will try and tell you some of the trials and tribulations of an old pioneer of Idaho.

I did not come to Idaho in a taxicab, nor in a Pullman car. On the 29th day of April, 1862, I mounted the hurricane deck of a cayuse at Yreka, California, and started through Shasta Valley on the Klamath Lake trail for Salmon Basin or Florence Diggings. It was snowing like blazes. I was camped at Klamath Marsh on the 10th day of May. I arrived at Florence on the 3rd of July, and it was still snowing.

We had some interesting experiences on the trip, pleasant as well as unpleasant. Every Indian camp we came to, the chief wanted grass money; he would collect 50¢ or $1 from each man in the company, for the privilege of traveling through the entire Klamath Lake country. The next camp we would find, another chief would go through the same game and of course we had no written agreement signed by the first chief to show that we had any privileges at all, so we had to potlatch.

While we were parleying with the chief about the grass, a brave would jump into a canoe, with a dip-net front, and take a little circle around from the lake shore, and bring out a string of fish; it took 25¢ to buy the string. If there were two or twenty, it made no difference about the number.

Find Plenty of Water.

It was not the best time in the year to travel through that country, as the snow had not all melted off the trail, and the ground was just thawing out. Mire a saddle blanket! Well, we found places where we had to unpack, spread blankets and roll a horse on the blanket to snake him out of the mud. We got into one place where we had to camp and cut brush to corduroy for three or four miles and lead our horses single file to get through. I was, as usual, detailed to watch camp; there were two parties of us here, one party from lower California. The man left at camp to watch their goods was an old saloon keeper, and had with him the necessary ingredients to make any kind of liquor he wanted. He said if I would furnish the water, he would do the balance, and we would give the boys a treat when they came in from work. The only show to get water was from a snowbank near the camp, so I gathered all the iron camp kettles I could find and soon had two or three gallons of water melted over a pine chunk fire; in a few minutes he had as many gallons of first class whiskey ready for use. When the boys came in they all bragged on the stuff, but they could all notice the flavor of pitch pine smoke.

When we left this camp, we soon got out of the swamp and had better traveling, better feed, and everything was gay. All the creeks coming down the mountains were very high and we had to travel the high water trail. The Deschutes was out of its banks, and the low bottoms were covered with water from 6 inches to 10 feet deep. After several days travel we came to where we had to cross the river. Here we found two men from Yreka, who had camped and dug out a canoe and were ferrying men and their goods over for $1 per man and his outfit; they wanted another boat so my partner and I took the contract and dug out another canoe for them. When we had the canoe about finished—it was on the opposite side of the river from camp—the four of us got into the old boat early in the morning and went across to put some finishing touches on the new boat and bring her over; about the time we got her to the bank, ready to launch, a party of 20 or 30 Modoc Indians came up from The Dalles and wanted to cross the river, but would not pay anything for it, and the owners of the outfit did not want it that way. After pow-wowing around awhile, they found out we had left our firearms in camp, and told us the boats belonged to them, and they made us know they meant it by bringing out their old muskets, bows and arrows and said they would take the boats and cross the river anyway. I was the only one in the party who could understand what they meant and who could talk with them, and because I could not get the owners of the outfit to take them across, I came near losing my life.

Treaty With Indians.

We acknowledged their right to the country, and finally succeeded in making a treaty whereby we took one boat and went to camp and they took the other and ferried their goods over that afternoon, and we all camped together in peace that night and parted friends the next morning.

The Indians started early in the morning for their home at Klamath lake, and we gathered up our stock and put them across the river, loaded the camp outfit, blankets, grub, pack saddles etc., into the two canoes and one of the ferrymen took one boat and I took the other; the other ferryman and my partner took the horses and we moved down the river 5 or 6 miles to a better crossing that we had discovered a few days before.

We had some fun shooting at beaver that the high water had driven out of their houses, but we did not get one beaver.

The next morning my partner and I hit the trail again. We traveled down the Deschutes several days, crossing Swift River, Tye Creek, and other creeks coming down from Mt. Hood, and passed Warm Spring Reservation; here was an Indian school, white men teachers, with about the usual number of pet Indians lying around. It was a fine place to bathe, beautiful location.

We traveled some distance further down, crossed the Deschutes on a bridge made by laying two logs across the chasm and covering with poles so as to lead the horses over it, toll, 25 cents a head. We then struck out across the country for Walla Walla, crossed the John Day river, Umatilla river and Walla Walla river.

Our lower California traveling companions and my partner visited the city on Sunday, undertook to paint the town red, failed and some of them took rooms with the chief of police that night. My partner was one of the number who patronized the cooler. They all reported at the camp on Monday morning about 9 o'clock, a little dejected, but ready to move on, so we packed up and hit the trail for Lewiston. We had a wagon road now to travel. There was no stage line at that time, but a stage was put on that summer. Houses on the road were few and far between; a few farmers were settled on the Touchet, and there was a fine farm near where Dayton now stands, I don't remember the name. We camped near the farm, and bought bread, milk, butter and eggs, which was quite a treat for weary travelers.

After we left Touchet, we traveled up Whetstone hollow, over into Petaha and down to Snake river, crossed Snake river [on a ferry boat, about 8 miles below Lewiston, crossed Clearwater river] near the mouth, and landed on Main Street in Lewiston. As this was the last supply station on the road, travelers bought what they wanted here not only to last them through, but to last awhile after they reached the mines, as everything was $1.00 a pound at Florence.

As money was getting short with the boys, some of them had to sell a horse to buy the necessary supplies. A man traveling with us named Joe Fugate, was the owner of a three-year old Mexican mustang pony, the pet pony of the gang. Joe would lash his little pack of 30 or 40 pounds, on and turn him loose to go as he pleased to the next camp. The pony would stop and eat grass until the caravan would get about out of sight, then start and see how soon he could overtake us. There was a Texas jockey traveling in the bunch who watched the pony pretty close, and when Joe offered him for sale at Lewiston, the jockey bought him for $30, and took the back track for California, trained his pony and put him on the track at Shasta, California, won a $2000 race and sold the pony on the ground for $3000[$2000]; but I am off the track a little myself, telling stories on the side.

We all supplied up as well as we could at Lewiston and hit out on the beaten trail over Craig's mountain onto Camas prairie to Whitebird, then to Salmon river; up Salmon river to the mouth of Slate river [creek], and over the mountain to Florence, arriving July 3, 1862. I thought it was the dullest mining camp I had ever seen, to make so much fuss about. I met several friends from Yreka who had got there ahead of me and they were all idle; in fact there seemed to be more idle men, than there were at work. The Buffalo Hump bubble had exploded, and men were coming in gangs from that wild goose chase.

There was a good deal of talk about a new camp struck, called Elk city. Jim Warren had just struck diggings 35 or 40 miles south of Florence, called Warrens diggings. Most of the men in the camp had got stung in the "Buffalo Hump stampede", as the Dutchman called it—and were loath to start out on another chase through the mountains.

On the Fourth of July, there were a great many people gathered in Florence, of all classes from honest to three card monte men. Mose Milner and Happy Jack, amused the crowd with gun play, emptied their revolvers at each other in the crowded street, but nobody was hurt.

Spanish Rube was running a three card monte in front of Boston's saloon and everybody seemed to be happy.

About the 6th of July, I went to work for a man by the name of Sam Swinehart, on the Sand creek; my partner would not work for wages, he would rather play poker and cultice around town. He took a trip over to Warrens diggings, and looked around there a few days, but did not find anything to suit him, so he went down to Walla Walla, and late in the fall came to Boise basin and located mining claims at Placerville. I continued working until late in the fall, at $6 per day. In October, some one stole my two horses and left me a-foot. Mr. Swinehart concluded to go to Boise basin, so a young man by the name of Thomas Munday and I pooled our capital and bought him out. As we could not work the ground through [the winter months, we concluded that one of us would stay and watch the claims and the other would go outside for the winter, so we worked until we took out money enough to buy supplies for the one that stayed, and enough to pay for the others expenses to Walla Walla. Mr. Munday agreed to stay and hold the claim down. I fell in with some friends, Duke McCalister and Tom Masterson, and we make up a "mess" and traveled together. I had a saddle and no horse; they had a horse and no saddle, so we spliced up and packed our grub and blankets on the horse and footed it down to Lewiston; we had plenty of company and a jolly time. There were miners working their way out to a warmer climate for the winter, some on horseback, some afoot, some traveling nights and some days; we heard of someone being robbed nearly every day. Three men passed us every night between 11 and 12 o'clock; they were Bill Mayfield, Mat Graham and John Donavan. I don't know why they traveled nights; the first night they passed us at Capt. Durkee's place; there were 12 or 15 of us sleeping in the barn yard, and while these men were eating supper, Captain Durkee came to the barnyard] and quietly wakened every man told us to look for ourselves, said they had just come in and did not know why they traveling at that time of night, and was afraid they meant mischief. I think Mayfield was afraid to travel over the road in the daytime. One night we were sleeping on the floor in a roadhouse and these men came in about the same time, got their drinks and ate their lunches. As they started out, I heard Mayfield say, "I wish to God I could lie down and sleep like those men".

When we arrived in Lewiston, we found the town under control of the Vigilance committee. Bill Berry, a prominent man running a pack train into Florence, had been robbed on the trail about the time we started out. They followed up the robbers and arrested Nels Scott and Billy Peeples in Ball and Stone's saloon in Walla Walla. Dave English took a by-trail down the Touchet, and Berry and the sheriff headed him off, and arrested him in Wallula.

The people of Lewiston got together and formed a Vigilance committee; the town was full of strangers, miners, gamblers and thieves, making their way from the mines down to the lower country for the winter. Everybody was excited; the citizens of the town did not know who to trust. Berry and the sheriff were bringing the robbers up to Florence for trial, and the Vigilantes had organized to try them in Lewiston. We arrived in town on Wednesday, and the prisoners would come up on the stage Friday and have their trial on Saturday, and of course we stayed over to hear the trial. The stage came in on time, about 6 p. m. The vigilantes were at the hotel, and when the stage drove up, 50 armed men surrounded it and told the sheriff they would take charge of the prisoners; he made some objection, but they agreed to take care of them till morning, and give them a fair trial. The Vigilantes court convened at 9 o'clock Saturday morning; the jurymen all answered their names and were sworn; then the trial began.

The prisoners had the best lawyers in Lewiston to defend them; they claimed they had witnesses in Camas Prairie, by whom they could prove an alibi. The lawyers asked for postponement to give them time to get their witnesses, Judge Johns granted the plea and postponed the trial till 10 o'clock Monday morning. A good many of the committee were opposed to postponement and had quite a pow-wow over it after court adjournment, but things quieted down and everybody seemed satisfied except old man Marshal and Tom Gafney. Marshal raised Peeples from a child, he said he did not care what they did with the other two, he would get Peeples out anyway.

The prisoners were put back into the log cabin, and guarded by 50 armed men. About dark, old man Marshal and Gafney undertook to break through the guards to get Peeples out. Marshal and one of the guards exchanged shots, and both got hit; the bullet from the guard's gun cut a furrow through Marshal's scalp on the top of his head; Marshal's bullet struck the guard in the side. Firing the two shots caused the wildest excitement. Both men fell, men came running from all directions. The wounded men were soon taken to doctors' offices and had their wounds dressed, and Gafney hid himself, while the Vigilantes doubled their guard. The excitement quieted down, and everything was as quiet as a graveyard.

The next morning, Duke McCalister and I went to the hotel to get breakfast, and we heard they had hung the prisoners in the night; without waiting to eat breakfast, we hurried down to the jail, found the door open, the guards gone, and everything as peaceful as though nothing had happened. We looked inside and there the three men hung to the joist, the chains on their legs not off the floor; a sorrowful sight to behold.

The vigilantes accomplished what they started in to do, that is, to break up the supposed band of "Road Agents" that had been terrorizing travelers on the trail between Lewiston and Florence all summer. They appointed a committee to rid the town of undesirable citizens; this committee notified several men that their presence was not needed in the city, and they did not wait for a second order. Tom Gafney was one of the first to obey that order. My friend Duke McCalister and I did not wait for an order; we took the first chance that offered, found enough miners going our way to make a party of seven, and hired a wagon, team and driver to take us to Walla Walla for $5 each.

We left Lewiston about 11 o'clock a. m., and those men were still hanging in their little cabin. We fell in with a good crew to travel with camped out nights, did our own cooking and had a jolly time.

Our driver on this trip was John Billings, one of the vigilance committee that helped to do the hanging act. He claimed to be the man who tied the rope around Peeples' neck; also claimed to have been one of Ben Holiday's riders on the pony express. He went to Boise basin in 1863, disappeared from there in 1866, was arrested in Oregon for stage robbery, convicted, and died in the Oregon penitentiary.

[Tom Gafney, who accepted an invitation from the regulators to leave Lewiston, reached Walla Walla before we did. He was in Walla Walla but a short time when he got into trouble with a Jew and was killed and buried by the city. "Peace be with him".]

My friend McCalister and I remained in Walla Walla waiting for something to turn up until we went broke; could not find anything to do to make "grub"; 25 men for every job, so we went out on Walla Walla river and rented a little old log cabin for $4 per month for the winter, paying the rent by cutting cord wood; our bill of fare was bread, bacon, beans, and once in a while, a mess of dog salmon, when we were lucky enough to shoot one in the river. We went to work and cut enough wood to pay the rent for three months; he allowed us $2 a cord for cutting wood to pay the rent, but would not give us anything for cutting any more, so we only stayed there about a month, when we settled with the old man, called it square for the rent and on the 16th day of January, 1863, hit the trail for Boise Basin.

Hit Trail for Boise.

We met a friend from Florence, Ben Irwin, "A man from Arkansaw," who was on his way up to the Basin; he was the owner of a pony, and agreed to pack the outfit for the three of us on the pony and take a walking chance with us.

We started out gay and happy, camped first night on Umatilla river at the foot of the Blue Mountains; next morning started up the mountain on the Meacham trail, we soon struck snow, but the trail was broke. The snow was three or four feet deep on the mountain, but the trail was fairly good, and we reached Grand Round valley on the third day out. There was very little snow at LaGrande, but we found out that the snow got deeper from there, for 75 or 100 miles, and no feed for the horses, and the snow was piling up by daily storms, so we went down on Grand Round river about 3 miles below LaGrande and made camp. We had an addition to our bunch of tramps of three men, James Cameron, Ed. Balldock and George Pierson, in the same financial condition as ourselves, all of us beating our way to the new diggings 200 miles away. We had no tent so we built a sort of wicky-up of poles and covered it with rye grass, which made it quite comfortable. We all slept in one room and ate at the same table.

We remained at "Hotel-De-Rye-Grass" until the grub gave out, then all except the man from Arkansas rolled up a couple of day's rations in our blankets, strapped on pan and coffee pot, and hit the trail. We camped that night on a little creek between Grand Round and Powder River valleys. After supper we borrowed a shovel from some packers and scooped out as warm a place as we could find in the snow, spread our blankets, turned in and slept fine until daylight. [When we crawled out, we found about 4 inches of snow. We found some dead willows, made a fire, boiled a pot of coffee, ate some dry bread, drank a cup of coffee, and rolled up our blankets and started out. We waded from 10 to 15 inches of snow that day to Pocahontas and camped there for the night, stopping at a miner's place who gave us permission to cook over his fire and sleep on the floor, which was very acceptable.]

The next day we reached Auburn late, and went to bed on a scanty supper. We camped in a corral and had the privilege of sleeping under a shed. We got up feeling pretty blue. One of the boys went up town and came back with 3 loaves of bread and 3 pounds of beef steak, the first square meal we had since we left the "Hotel-De-Rye-Grass". We were trying to save $2.00 or $3.00 in the bunch for an emergency such as ferriage etc.

We rustled all that day for a grub stake, without success; the next morning, I called on a gentleman from Yreka, California, Albert H. Brown, who owned a store in Auburn. I told him our situation; he heard my story and said we could have [what we wanted. We got a sack of flour, yeast powder, coffee and] a chunk of bacon, $20.00 in all, which we took to camp and divided into five as near equal parts as we could, then each took his share and fixed his pack to suit himself. When all was ready we shouldered our loads and walked. We had to wade from 10 to 15 inches of snow, and after we struck Burnt river, we had to wade that two or three times each day, all the way from one and one-half to two and one-half feet deep, yet we were as jolly as though everything had come our way at last.

When we reached Snake River bottom, the snow was not quite so deep, but it snowed and rained just as regular. We left Burnt river and traveled the old emigrant road, passed Tub Springs to Washoe ferry, where we had to cross the Snake river. [The Ferryman was camped on the opposite side, so we yelled till they heard us and brought the boat over and took us across and gave us our dinner, and when we offered to settle, they said there was no charge, that we had a hard enough time traveling in that style without paying for the privilege. They warned us to look out for Indians for they were shooting into camps and had crippled a man the night before, two or three miles up the river from the Ferry. We thanked them for their kindness and advice and hit the trail for the Payette Valley. We traveled until about 10 o'clock that night, went out about a hundred yards or more from the trail and made our beds in the sage brush to dodge the Indians and did not dare to make a fire.

It rained all that night. The next morning we got up and packed our wet blankets 9 or 10 miles up the Payette River before we got our breakfast. That night we camped at Picket Corral, where some men were looking after a bunch of horses. They had built a log house and a kind of picket corral to hold the horses at night and to keep the Indians from stealing them. The Indians had run off a bunch of their horses the morning before we got there, after they had turned them out of the corral, while the herder was eating his breakfast.]

We reached Horseshoe Bend from Picket Corral about 11 o'clock a. m.. Here we found the first bare ground since we left Walla Walla and the first bright sunny day. It seemed to us the pleasantest spot on earth. We spread our blankets and clothes out to dry and stayed here until the next morning; had a good rest, and started early in the morning over the Jackass trail for Placerville. We soon struck the snow and traveled over snow that day from six inches to seven feet deep, but the trail was good as there were pack trains going over the trail every day packing supplies in to the miners.

We reached Placerville on the 21st day of February, 1863, about 9 o'clock in the morning, each of the five able to answer roll call and line up to the bar in Jeff Standerfer's saloon and take a good big drink of tanglefoot.

As Placerville was only a tent town it was too late to find quarters for that night, so we went up to the west end of town and camped together for the last time. I could not find the spot now and I think I am the only one of the five now living. Ed Balldock was accidentally shot and killed at Idaho City in April, 1863; James Cameron and George Pierson I have never seen since that summer of 1863. Duke McCalister died in Idaho City in 1890 and I think that S. M. Sisk is the only one of that bunch of tramps who lives to tell the tale, as far as I know at this time, September, 1913.

The years of my life passed in Boise Basin from February, 1863, to October, 1879, is so similar to the great majority of poor miners and disappointed gold hunters that the tale is hardly worth telling. The first break was a bad one. I met my old partner from Yreka, Cal., who had reached the basin in the fall of 1862 in time to locate mining ground in favorable localities and he offered me one half of his interests at a very reasonable price, and agreed to let me pay for it as I made it out of the ground (of course I had no money to pay down), so I accepted his offer and went to work. The ground paid well, so I was soon out of debt. But prosperity did not seem to improve my partner; he stayed with his old habits of drinking and gambling and managed to keep both of us broke all the time, so in September, 1864, I sold my interest back to him on the same terms, and we separated again. I went to Idaho City and went to work for wages, he remained in Placerville and worked the ground through the mining season of 1865. In the spring of 1866 he sold out and went to Montana during the winter of 1866 and 1867. He killed a man in a drunken row and the vigilantes hung him, thus ended the career of a man who meant well, but who could not resist the temptation to indulge in whiskey and cards. He left me holding the sack for about $2500.

I worked for wages at Idaho City most of the time till in 1879. On December 3, 1874, I was married to Miss Lizzie Moore at Idaho City; in October, 1879, we moved to Walla Walla, Washington Territory; in 1880 we moved near Sprague Washington Territory, built a house on a 160-acre claim that proved too dry to live on; in l881 sold the improvements, leased a farm near Steptoe Butte, and in 1882 raised a fair crop; in the spring of 1883 sold the lease and worked on the Palouse branch of the Northern Pacific railroad; in June 1884, we moved back to Idaho City, then in 1885 we moved to Long Valley where we stayed until 1908, when we moved to Boise, and here we are after many ups and downs, and with the help of God and other friends we are here to stay.

Source: Idaho Statesman. (Boise, ID), September 7, 1913, pages 1,3; September 21, 1913, pages 3,4; September 28, 1913, pages 5,10 - GenealogyBank.

[In the original document, but not included in the newspaper article.]